The umbilical cord—this remarkable cable of life—often prompts worries and a flood of questions for parents: Is it safe? How does it help my baby? Why do doctors discuss cord blood and the timing to cut it? Many caregivers are anxious about knots, loops, infections, or even how to care for that tiny stump left on the belly. If you are pondering what does the umbilical cord do, you are not alone in searching for clarity on its role and the choices you may face from birth to first weeks of your child’s life. Here is a deep dive into the function, structure, complications, and practical care of the umbilical cord—filled with clear explanations and science-backed insights—to help you feel more confident and informed as you support your newborn, from womb to world.

What does the umbilical cord do? Quick answer for parents

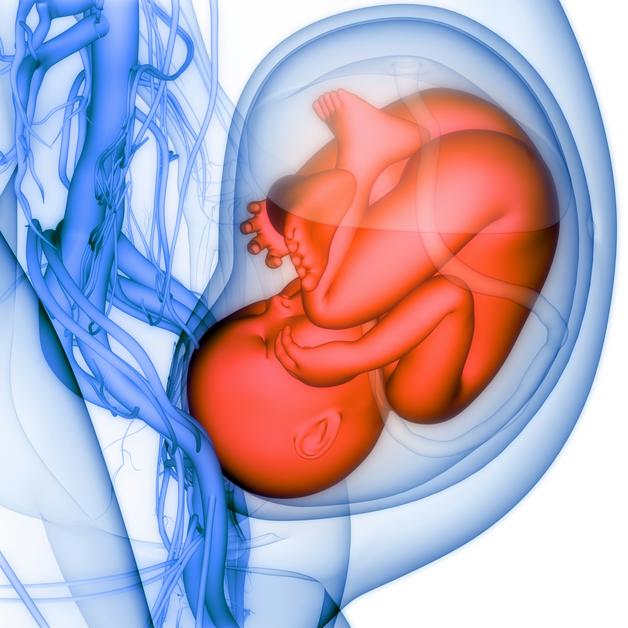

The umbilical cord is not just any connection—it is your baby’s true lifeline, the direct link shuttling life’s essentials back and forth during pregnancy. In plain words: what does the umbilical cord do? It brings oxygen and nutrients from the placenta to the baby (through a single, large umbilical vein), while at the same time it whisks away waste and carbon dioxide through two umbilical arteries. Picture it as a bustling bridge: nutrients, oxygen, and even immune factors—yes, maternal antibodies for early protection—travel in, while waste makes the return trip out.

On ultrasound, this cord may look simple, but inside, it is more complex—cushioned by Wharton’s jelly (a jelly-like substance that prevents kinks even as the baby twists and turns) and wrapped securely by the amniotic membrane for added support. The timing of when the cord is clamped and cut at birth plays its own role in how much blood (and hence iron and red cells) your baby keeps, influencing anaemia risk and immediate circulation. Wondering if those minutes make a difference? For many babies, a brief wait before clamping allows a last, precious transfer of blood.

Anatomy: What the umbilical cord is made of

Dive beneath the smooth, pale surface and you’ll find a fascinating design—three blood vessels (one vein, two arteries) running side-by-side, embedded in that gelatinous Wharton’s jelly. Why not more, why not less? In fact, this very layout is vital for uninterrupted blood flow even in the cramped, ever-changing conditions inside the womb.

- The umbilical vein (the big one) carries oxygen-rich, nutrient-packed blood from the placenta to your baby.

- The two arteries (smaller, duo) return deoxygenated blood and waste to the placenta for removal via your own circulation.

- Wharton’s jelly acts like a shock absorber, protecting these vessels from compression, pinching or twisting. Nature’s own cushioning!

- The sheath—the amniotic membrane—seals the cord and provides another layer of security.

The length and coiling of the umbilical cord can vary: most are around 50–60 cm, long enough for baby’s movement, but not too long to loop excessively or tie knots. If you encounter phrases like “central insertion” or “velamentous insertion,” know that these describe the spot where the cord joins the placenta—some positions are routine, while others may require closer monitoring.

Curious about sensation? The umbilical cord is free from sensory nerve endings—meaning when it is cut, your baby feels nothing at all.

Physiology: How the cord supports fetal circulation and growth

The logic is extraordinary: what does the umbilical cord do physiologically? It serves as an efficient highway for exchange—blood flows from placenta to baby and back, ensuring oxygenation and removal of waste. The umbilical vein’s blood is rich in oxygen, facilitated by fetal haemoglobin (which, compared to adult haemoglobin, clings to oxygen molecules more tightly, perfect for the low-oxygen journey).

Through the placental barrier, oxygen and vital nutrients move mostly by diffusion, but other substances—amino acids, glucose, some ions—need active or passive transport mechanisms. Even maternal IgG antibodies are shuttled through (especially late in pregnancy), providing crucial immune protection.

During labour, uterine contractions temporarily squeeze this placental link, sometimes resulting in “variable decelerations” on the fetal heart tracing (those temporary drops doctors track). Normally, good cord structure resists interruptions to blood flow, but tight compression can alter cord gases—the pH and other values measured immediately after birth to reveal how well the baby coped with labour.

Embryology and cord development: How does this marvel form?

Let’s go back to the very beginning. During early pregnancy, what does the umbilical cord do—or rather, how does it start? The earliest version of the cord evolves from what’s called the “connecting stalk,” merging with contributions from the allantois and yolk sac. By the end of the 1st trimester, those all-important vessels inside the familiar jelly sheath have formed, and normal coiling patterns start as the fetus moves and blood pulses.

Any pronounced change in this coiling (either too tight—hypercoiling—or too loose—hypocoiling) may point towards growth problems or risk of complications, and may decide how closely doctors track the pregnancy.

Role during labour and delivery

Parents often wonder: what does the umbilical cord do while the drama of labour unfolds? The cord is engineered for resilience but, under the squeeze of contractions, may still be compressed. Loops around the neck (nuchal cord) are more common than one may think. Most babies with a simple loop arrive healthy, thanks to the cord’s protective design. However, a tight loop, true knot, or abnormal insertion may alter the fetal heart rate, calling for even keener medical attention.

The choice between delayed cord clamping (DCC)—waiting 1–3 minutes before clamping and cutting—and early clamping has become prominent. DCC allows more placental blood (and iron stores) to reach the newborn, especially reducing the risk of anaemia. Exception: life demands speed when there’s bleeding or the newborn needs urgent resuscitation.

After clamping, the cord’s pulsation eventually ceases as the baby begins to breathe and cardiovascular pathways change, supporting the shift from placenta-based to lung-based oxygenation.

Cord blood, cord tissue, and post-birth options

After birth, a new set of queries pop up—what does the umbilical cord do now? The leftover cord blood is an impressive resource: it contains hematopoietic stem cells, which can regenerate blood and immune systems. These are sometimes collected (for donation or private storage) for potential future treatments, notably in blood cancers or genetic conditions. Delayed clamping, while excellent for baby, means less cord blood is available for banked collection—a point worth discussing with your care team if you’re considering this route.

Beyond the blood, Wharton’s jelly in the cord is rich with mesenchymal stromal cells. The promise here is mostly in research—these cells hold future potential for regenerative medicine, but routine clinical use is yet to become standard.

Private cord blood banking remains a personal, and often financial, decision; public donation builds a registry for patients in need, but does not reserve the unit for your child specifically.

Variations and common cord complications

Nuanced and occasionally anxiety-inducing, umbilical cord variations deserve attention. Wondering what does the umbilical cord do if things aren’t textbook?

- Nuchal cord (neck loop): Common, mostly benign unless too tight.

- True knots: Rare, especially risky only if pulled tight.

- Velamentous insertion: Vessels run through the membranes unprotected, raising bleeding risk—ultrasound can sometimes diagnose this before birth.

- Vasa previa: Fetal vessels cross the cervix—a dangerous situation requiring planned caesarean, if found prenatally.

- Single umbilical artery: Instead of two, only one artery is present. This points to a need for extra monitoring, as there can be increased risk of anomalies.

- Short or long cord: Both extremes can cause delivery challenges—short cords can restrict movement or complicate birth; very long cords may tangle, knot, or even prolapse.

- Hypercoiling / hypocoiling: Markedly abnormal twists increase the risk of adverse outcomes; close fetal surveillance is indicated.

Cord prolapse, where the cord slips down during labour and gets compressed, is rare but rapidly life-threatening—a swift, skilled response is vital to protect the baby’s oxygen supply.

Diagnosis and monitoring of cord health

Modern pregnancy care has advanced tools: routine ultrasound checks for vessel count, insertion site, and obvious knots or loops. However, visualization isn’t infallible—not every detail is visible, and findings are interpreted in context with fetal growth and heart tracings.

Doppler velocimetry—ultrasound assessing blood flow in the umbilical arteries—produces indices that reflect overall placental health. Abnormal results, like absent or reversed end-diastolic flow, are warning signs for placental insufficiency. Cord blood testing at birth provides an acid-base status snapshot—vital in guiding neonatal care if labour has been particularly challenging.

Management if the cord is compromised

What should be done if problems are seen or suspected? Maternal positioning (left lateral, or knee-chest), oxygen, IV fluids, and sometimes amnioinfusion (fluid added around the baby to cushion the cord), can buy time during delivery. In the case of a tight nuchal cord, the medical team may try to gently reduce the loop; with cord prolapse, immediate action and likely caesarean is warranted.

Known risks—such as vasa previa—drive a coordinated, multidisciplinary plan for the birth. Newborns with evidence of significant events (low Apgar score, abnormal gases) may need advanced care, sometimes in the NICU, with close developmental follow-up.

Umbilical cord stump care after birth

Once home, attention shifts to the tiny stump—what does the umbilical cord do now, after being cut? Over the next one to three weeks, the stump dries, darkens, and painlessly drops off (often by day 7). Signs of infection—persistent redness, swelling, pus, or a delay beyond three weeks—warrant contacting your healthcare provider.

- Keep the area dry and clean.

- Fold the diaper below the stump to avoid irritation.

- Sponge baths until separation is ideal.

- No need for antiseptics or special powders, unless specifically advised.

Never pull on the stump—it will fall off when ready. The navel (belly button) continues healing after detachment, sometimes leaving a small spot or oozing for a few days.

Cultural, ethical, and practical considerations

For many families, the cord is more than medical—it holds cultural and symbolic meaning, featuring in rituals, keepsakes, or ceremonies. Some traditions call for placenta burial, others for cord preservation for spiritual reasons. It is wise to discuss these preferences with your obstetrician in advance.

Cord blood banking—private versus public—is a question of need, cost, and consent. It is best finalised before labour, especially since timing of clamping and delivery logistics are involved.

Finally, hospital practices differ: who cuts the cord, procedures for banking, and what paperwork is needed should be clarified in the last weeks of pregnancy.

Key Takeaways

- The answer to what does the umbilical cord do is both simple and intricate: it links mother and baby, ensuring the transfer of vital oxygen, nutrients, and immune protection—then removes waste—until the moment your newborn breathes independently.

- Anatomical strength—protected vessels, ample jelly, and optimal coiling—guards against most daily mishaps, but variations like abnormal insertion, knots, or compression can alter monitoring or delivery approaches.

- Delaying cord clamping can enhance early blood volume and iron, but must be balanced with urgent needs or cord blood collection plans.

- Cord blood carries cells with established potential in treating serious medical conditions; use of Wharton’s jelly is largely experimental.

- Surveillance—ultrasound, Doppler, and heart tracings—spotlights most significant cord health issues during pregnancy and birth.

- Day-to-day stump care is another chapter: keep it dry, clean, and gentle, and watch for rare signs of infection or delayed healing.

- Many families find comfort in blending medical choices with personal or cultural traditions around the cord.

For extra confidence, know that you can access expert resources and receive tailored health advice for your family by downloading the application Heloa—a valuable ally with free health questionnaires and tips for children, designed to support your parental journey with clarity and respect.

Questions Parents Ask

Is the umbilical cord attached to the belly button?

Absolutely. The umbilical cord attaches directly at baby’s abdomen—exactly where the belly button will someday be. After birth, once clamped and cut, that little stump dries and falls away, revealing the navel. Curious or worried about pain? Rest assured, no pain—the cord has no pain nerves, and the belly button is simply the gentle scar left after separation.

What happens to the umbilical vessels and cord tissue after birth?

The transition is fascinating: after the cord is clamped and trimmed, blood stops flowing, and the outer stump gradually dries up and falls off. Inside, those vessels transform into harmless fibrous bands—the umbilical vein becomes the round ligament of the liver, unused arteries become ligaments too. If considering donation or cord blood storage, it is arranged before or just after birth, since timing of clamping changes how much blood is available for collection.

Why is cord blood sometimes collected?

Because cord blood is rich in hematopoietic stem cells—capable of creating new blood and immune cells—it’s a valuable resource used mostly for transplantation in certain medical conditions. Some parents choose banking for future family health needs or donate to public banks for wider community use.

How do I know if the cord stump is healing well?

Normal healing means the stump dries, shrivels, and falls off in 1-3 weeks—often by day 7. Keep watch for redness, swelling, warmth, pus, or foul smell, or if it’s still attached after 21 days. Fever in a newborn is always a reason to contact your paediatrician.

Is it okay if the cord was around the baby’s neck at birth?

Nuchal cords—loops around the neck—are surprisingly frequent and generally harmless if not too tight. Medical teams check for distress or tight compressions, but for the majority of babies, a simple loop requires no extra intervention.

Does the cord stump require special cleaning?

Usually, gentle washing and drying is enough. Avoid powders, antiseptics, or home remedies unless your provider specifically suggests them. Aim for dry, clean care and let it drop off on its own.

Can I save the cord for traditional or religious reasons?

Many families choose to keep part of the cord or have a special ritual, whether for spiritual, symbolic, or cultural reasons. Most hospitals accommodate such practices, as long as hygiene and safety are respected. Discuss your wishes early with your care team for a smooth experience.

What if I have more questions about cord blood banking or birth practices?

Connect with your healthcare team—they can help you weigh options about cord blood collection, delayed clamping, and family traditions. For additional clarity and support, try the application Heloa for tailored answers and child health tools.

Further reading:

- Anatomy, Abdomen and Pelvis: Umbilical Cord – NCBI: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK557389/

- Umbilical cord care: Do’s and don’ts for parents: https://www.mayoclinic.org/healthy-lifestyle/infant-and-toddler-health/in-depth/umbilical-cord/art-20048250

- Blood Circulation in the Fetus and Newborn – UR Medicine: https://www.urmc.rochester.edu/encyclopedia/content?ContentTypeID=90&ContentID=P02362