Flat spots on your baby’s soft head—ever noticed them and wondered if it’s something to lose sleep over? The sight alone can make any parent’s heart squeeze. Questions multiply: Is this just cosmetic? Will my child’s brain be okay? What did I do wrong? Positional plagiocephaly—sometimes called flat head syndrome—invites a swirl of doubts, but with knowledge, much of this anxiety softens. Here, clarity on causes, how to spot telling signs early, what daily care can truly prevent or improve the situation, when therapies help, what science says about long-term effects, and above all, why no parent is ever to blame. Let’s untangle this with both method and empathy.

What Is Positional Plagiocephaly?

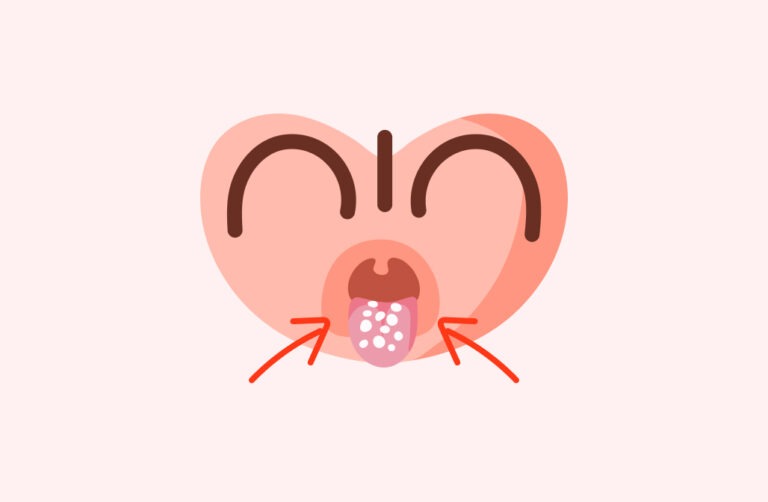

Positional plagiocephaly refers to a flat or asymmetrical area on your baby’s skull. It shapes up not from something “inside” like a brain problem, but outside pressure—imagine the gentle yet persistent molding of a soft clay pot. That skull, alive with growth and change, is most vulnerable in early months when babies spend so much time lying on their backs. Over time, consistent pressure in one area flattens part of the skull, which may create not only a misshapen appearance but, occasionally, other subtle shifts: one ear moving slightly forward, a cheek appearing a bit fuller, a forehead just a touch more pronounced on one side.

It’s worth distinguishing: not all head shape changes are alike. Brachycephaly means the entire back of the head is symmetrically flat. Dolichocephaly denotes a longer, narrower head—seen often in side-sleeping or premature babies. Far less common, craniosynostosis (premature fusion of skull sutures) is an altogether different entity, requiring specific evaluation.

Why Does Positional Plagiocephaly Happen? (And Who Is at Risk?)

The reasons are rarely mysterious, though sometimes invisible before a parent’s eye. Here’s what tends to tip the balance:

- External pressure: Day after day, night after night—lying flat on the back, in one favourite position, turns pressure into shape.

- Torticollis: Imagine a stiff neck that nudges baby’s head always to the same side. That habitual turning compounds the issue.

- Limited movement: Babies who aren’t repositioned frequently or who get little tummy time build up pressure in the same spots.

- Premature birth: Softer skull, more hospital time on the back, less chance to shift about—prematurity heightens vulnerability.

- Birth and womb influences: Less room to move in the uterus, long labors, forceps delivery—all can affect initial head symmetry.

Patterns stand out—boys affected slightly more, first-borns too, and those with long neonatal stays or medical conditions requiring less movement. But does it come down to parental error or neglect? Absolutely not; even with the best intentions and attentive care, positional plagiocephaly can appear.

Signs, Symptoms, and How to Spot the Difference

A gentle flatness seen around six to eight weeks—sometimes earlier. When peering from above, the head looks less round, more parallelogram. A sharp parent’s eye might catch:

- One ear closer to the face than the other

- Asymmetrical fullness of cheek or forehead

- A preference for turning the head one way

- Reduced ability to look both ways (especially if torticollis is present)

- Bulge of the forehead on the opposite side of flattening

Sometimes, these differences seem dramatic. Other times, they show up only on careful inspection.

Is Positional Plagiocephaly Just About Looks?

Parents grieve over the aesthetics—no denying that. But what about lasting consequences? Here’s what the best science says: the vast majority of cases are cosmetic, not functional. A minority, when left untreated and accompanied by other physical issues (like stubborn neck stiffness), might show slight delays in rolling, crawling, or balance. Worries about brain development or intelligence? To date, extensive research reassures—positional plagiocephaly does not impact cognitive, language, or intellectual progress. Only severe, untreated cases with dual complications might show mild physical or social effects later on.

Preventing Flat Head: Practical Tips for Parents

Is prevention possible? Absolutely. Even simple changes ripple towards a rounder head shape:

Sleep Time Strategies

- Back-sleeping remains essential for SIDS prevention. But alternate which way your baby’s head faces during each nap

- Regularly change the orientation of your baby in the crib—toys, light, parent position—all can draw your infant’s gaze in different directions

- Keep the crib clear of soft items: pillows, bumpers, blankets (safer, and allows freer movement)

Awake Time Action

- Supervised tummy time is a pillar—several sessions a day, starting from birth. Each minute counts

- Alternate arms during feeding, prompting your baby to look left and right

- Hold and carry your baby upright often, offering a change of perspective (and pressure)

- Limit time in car seats, swings, or firm carriers—essentials only for travel, not for daily lounging

- Encourage visually stimulating play from both sides; rotate toys often

Prevention isn’t perfection—it’s about consistent, caring variation. The more you change things up, the less likely pressure will have time to work its slow magic on those soft skull bones.

Diagnosis: When to Check and What to Expect

Every head shape makes a story, but not every story needs intervention. If flattening persists, seems to worsen, or is joined by a clear head-turning preference, consult a healthcare provider. The window between 3 to 6 months is the period of peak skull plasticity and hence, best outcomes with early care.

Diagnosis happens mostly by clinical eye and gentle palpation. Rarely, measurements such as the Cranial Vault Asymmetry Index (CVAI) may offer further precision. Imaging—X-ray, CT or MRI—enters the picture only if craniosynostosis is suspected.

Where needed, referrals to pediatric therapists or craniofacial specialists create a pathway for further support.

Management and Treatment: From Home to Clinic

Repositioning and Tummy Time

Simple, persistent at-home measures unlock progress in the majority of cases. Coupled with routine tummy time and position changes during sleep and play, the head gradually rounds out as motor milestones are reached.

Physical Therapy

When torticollis or restricted neck movement is identified, early physiotherapy helps—stretching programs, strengthening, and tailored exercises quickly restore symmetry and prevent escalation. Guidance from trained professionals ensures movements are gentle and precise.

Helmet Therapy (Cranial Orthosis)

Sometimes, home techniques can’t budge a moderate to severe flat spot. Between ages 4 to 6 months, custom-fitted cranial helmets—worn for up to 23 hours a day over several months—can guide the soft skull towards symmetry. This option is typically reserved for those with no improvement on consistent conservative measures. Decisions about helmets are highly individualized and based on specialist evaluation.

Surgery

Table this option—reserved only for cases where craniosynostosis is confirmed. For pure positional plagiocephaly, surgery plays no routine role.

How Long to See Improvement?

With timely intervention, most changes appear within three to six months. By age two, many children have rounder head shapes—sometimes, minor asymmetry may persist but becomes masked by hair growth or simply falls from notice with time.

Prognosis and Long-Term Outlook

A dynamic head for a dynamic child: as babies roll, crawl, and explore, posture evens out naturally. Long-term physical or psychological issues? Exceptionally rare and usually mild. Early, supportive management yields consistently positive outcomes.

Supporting Parents: Information, Compassion, and Next Steps

- Tracking progress—A simple “look from above” check as weeks pass can alert you to changes

- Staying curious—Varying positions, encouraging movement, and knowing when to ask for expert input, keeps things on track

- No room for guilt. Parental care is already working wonders.

- Cherish science and medical expertise—early steps are effective. Resources, support, and professional advice are abundant: from pediatricians to physiotherapists, help is just a question away.

Key Takeaways

- Positional plagiocephaly is widespread, visually significant, and, in the overwhelming majority of cases, benign

- Almost always, early, consistent movement and head turning bring visible improvements

- The golden triangle: Safe back-sleeping, dedicated tummy time, and alternating baby’s position

- Physical therapy targets stubborn neck tightness, maximizing improvement

- Helmets are reserved for special situations—never a universal solution

- Surgery pertains only to specific, rare skull-fusion conditions

- The science is clear: no effect on brain growth or intelligence

- There is a supportive medical community ready to guide families—explore application Heloa for tailored advice and free child health questionnaires

- Remember: Every baby’s head tells its own story—a few curves more or less never define a child’s future

Questions Parents Ask

Can positional plagiocephaly correct itself without intervention?

Many parents wonder if a flat spot will simply vanish as baby grows. In numerous cases, as motor milestones like rolling and crawling kick in, natural movements help round out the head. If flattening is mild and movement (like tummy time) increases, most children see gradual improvement. Still, with more severe or lingering asymmetry, introducing positioning techniques and consulting a paediatrician offer reassurance and direction.

Does positional plagiocephaly affect brain development or intellectual abilities?

A perfectly legitimate concern—nobody wants to miss a hidden risk. Rest easy: research shows positional plagiocephaly does not alter cognitive, intellectual, or developmental outcomes. If minor delays occur, they’re almost always linked to issues such as torticollis—not to mere changes in head shape itself. Keep a watchful eye on milestones, but confidence is justified here.

Are there any long-term effects of positional plagiocephaly?

Mild residual unevenness may persist in some children, but usually, hair and growth conceal this easily. Long-term functional, physical, or psychological issues? Exceptionally rare. Occasionally, visible asymmetry in later childhood may impact self-esteem, but for most children, minor differences are barely noticed. Parental responsibility is never in doubt: positional plagiocephaly arises commonly and responds well to early, positive action.

Further reading: